Michelangelo was gay (and other things we should know)

It turns out that queerness actually is…all around

An odd thought popped into my head recently as I was folding laundry:

Michelangelo was totally gay.

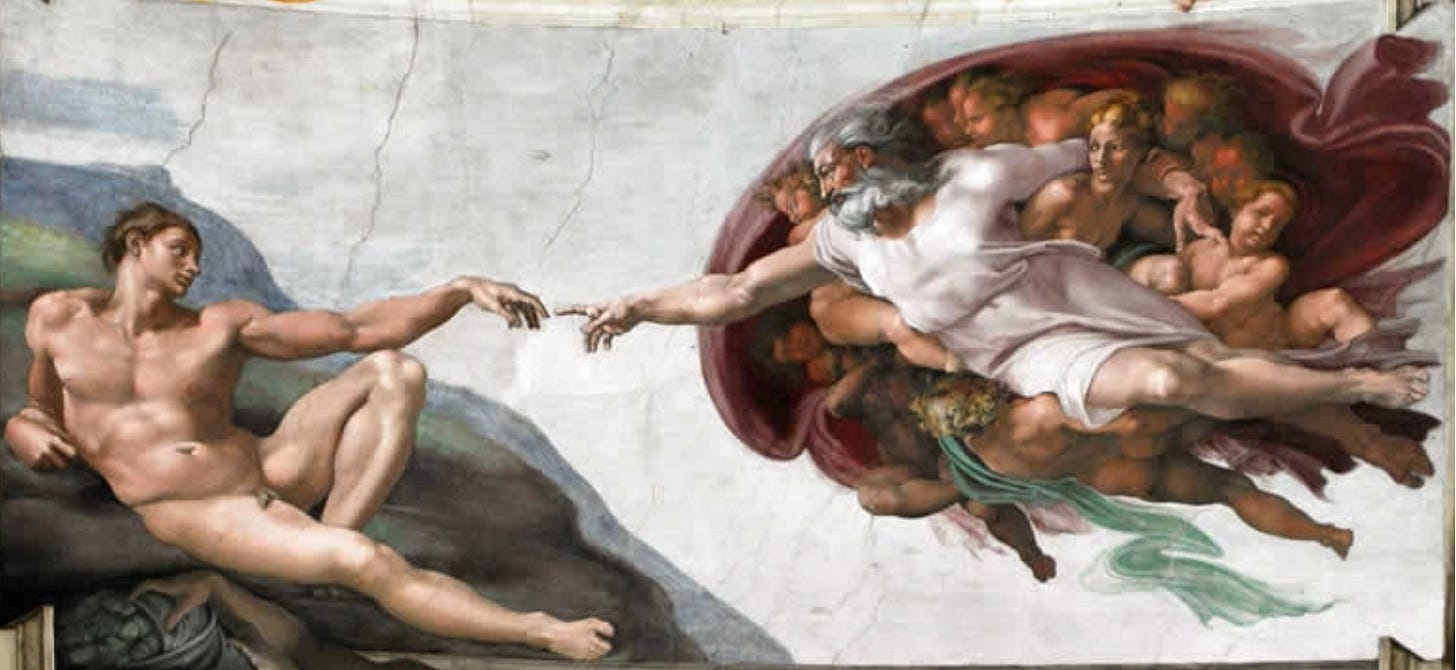

Michelangelo—famed artist of the Renaissance, painter of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, sculptor of the massive marble David with killer abs and the slingshot that took down Goliath—was queer.

It had never occurred to me before (why would it?). But as soon as it did, I felt sure I was right.

A quick search confirmed that I was.

Michelangelo, in the latter years of his life, had a close relationship with a young nobleman. The poems he wrote this man are so lustful that, after Michelangelo’s death, a family member went through the text and changed the male pronouns to female, so it sounded like they were written about a woman.

Once I had discovered this, I kept digging.

You know who else was queer? Leonardo da Vinci. Artist, engineer, scientist, sculptor, architect—one of humanity’s great geniuses. As a young man, he was charged under sodomy laws (the term used in those days) and put in jail. Historians argue about this —was he gay, was he asexual, did this early traumatic experience cause him to swear off relations with anyone? But it seems clear he was somewhere on the spectrum.

Also queer was Sandro Botticelli, who was charged in Florence for sexual activity with a young man as well (apparently a quarter of the men in Florence at this time had such charges on the books). This also gives us insight into why Botticelli’s female figures only look plausible when they have clothes on (he used male models). No 15th century Florentine woman ever looked like this.

I have an undergraduate degree in art history, yet none of this was mentioned to me.

Why am I talking about the private lives of famous artists? A good question.

Queerness is under attack right now. Here in the U.S., there have been 549 anti-trans bills introduced already this year (more than double from last year, and it’s only June). Anti-queerness is being used as a wedge issue to manipulate politics and gain power, but very real lives are being harmed in the process. Very real lives will be lost.

In a situation like this, I think it’s necessary for all of us to step up our education, to seek to understand what is going on and why.

And the truth (to borrow a phrase from the film Love Actually) is that queerness actually is all around. Often, it’s been deliberately hidden or oppressed, but it’s always been here. It’s part of the spectrum of human expression.

After my Michelangelo revelation, I went on an historical deep dive. Here is just a little bit of what I learned:

• The history of queerness starts at the very beginning of recorded human history. The first known references come from our earliest known civilization—Mesopotamia. In the temples of Ishtar, priests were bisexual and transgender. The Mesopotamian Almanac of Incantations includes prayers for both opposite sex and same sex unions. The Epic of Gilgamesh, a famous poem written in the Third Dynasty of Ur (circa 2100 BCE), features two male characters thought to be partners.

• In ancient Greece, bonded relationships between younger and older elite men were commonplace—the elders served as mentors in all spheres of life: philosophy, politics, poetry, and love (the older partner was called “the lover,” the younger “the beloved”). As James Flynn writes, in the magazine for the National Endowment of the Humanities, “The Greeks did not conceive of sexual orientation in our terms (e.g., as straight or gay): Later in life, men would be expected to marry women and to raise families.” But it does give a different read on all those naked men doing sport together.

• There is little mention of female same-sex relationships from antiquity—because there is little mention of women’s lives at all (thanks, patriarchy!). One exception is Sappho (630-570 BCE), the female poet from the Greek island Lesbos, from which the term “lesbian” is taken. What remains of her written work celebrates love between women, as well as with men.

• In ancient Rome, status was more important than anything else. A free-born man could have relationships with women, younger men, and groups below him in social status—slaves, prostitutes, or actors, male or female. Partnering with a man of his own rank, however, was not allowed—because one partner would have to lower himself. Numerous Roman emperors are thought to have been actively bisexual, including Hadrian, Nero, and Julius Caesar.

• In China there is a history of queerness as well. The first ten emperors of the Han dynasty (206-220 BCE) were openly bisexual, having a favorite male companion as well as their wives. “China had “a long history of dynastic homosexuality…” writes medical anthropologist Vincent E. Gil in the Journal of Sex Research. (Homophobia seems to have come in with the Mongols and the Manchus).

• Throughout the Polynesian islands, there is an established tradition of a third gender—not male, not female, somewhere in the middle. In Hawai’i they are called Māhū. According to a 2015 PBS documentary, “Māhū were valued and respected as caretakers, healers, and teachers of ancient traditions who passed on sacred knowledge from one generation to the next, through hulu, chant, and other forms of wisdom. When American missionaries arrived in the 1800s, they were shocked and infuriated by these practices and did everything they could to abolish them.” (That documentary is delightful, by the way).

• In Thailand, the Kathoey are a third gender, considered to have one body and two souls. Because Thailand is a Buddhist country and avoided the worst of colonization and Christian missionary influence, there is greater acceptance than elsewhere in present-day Asia. According to one article, “Tolerance and understanding are central Buddhist tenants, and there is even an explanation for transgender people in Buddhist mythology. Thai Buddhists believe that kathoey are women who were born as men in order to atone for sins committed in a past life; they are thus looked upon with pity and empathy rather than hatred or disgust.” There is discrimination, but there are also all-kathoey beauty pageants.

And there is so much more—the Kocek in Turkey, Hijra in India, Baklâ in the Philippines. Two-Spirit people of indigenous American traditions often served as healers, shamans, and ceremonial leaders. Spanish invaders used the accepted queerness in indigenous Latin America as a justification for conquest and slaughter. In Japan, same sex relationships were a common part of the Shinto religion, Samurai warrior culture, and Kabuki theater. It goes on and on.

Why do we not all know this?

Scholars warn that our understanding of historical queerness is limited—being “straight” or “gay” is a modern idea. Many languages did not have words to specify one or the other—people found pleasure where they found it.

There are cultures who considered gender to be the energy in a person, not the bits between our legs. Apparently, the Mbuti tribe of Central Africa did not bother with gender until a child reached puberty (prior to that point, is it even needed?). And many cultures have mythology about gods that are non-gendered or change gender.

The more I learn, the more it seems—rather than looking for the origins of queerness—we should be asking where heterosexuality and the gender binary come from. Why has that flourished?

[The answer, it seems: the church, colonialism, patriarchy, Islam, and capitalism.]

Hiding this history makes it easier to discount queer lives, it makes it easier to scapegoat and harm them. That harm is ramping up right now. And it’s not just in Florida and Texas. There are currently seven anti-queer bills in Oregon, two in Washington (check your state and track bills nationally here).

When we hide this history, we don’t fully understand who we are. Queerness illuminates our lives—in obvious ways, such as art and music and theater, but in non-obvious ways as well. Right now, it calls us to open our minds, to think beyond limitations, to protect all people. Theses truly are the most human(e) values.

Talking about this openly, understanding the larger context, is essential. So much has been hidden. It’s time to bring in the light.

Because queerness is not only our history, it is also our humanity.

Thanks for reading.

***

If you want to know more about current coordinated attacks on queerness in the U.S.—and the big money that is funding it—I highly recommend the podcast The Anti-Trans Hate Machine. If you don’t have time for the whole series, episode four (Money, Power and a Radical Vision) will clarify who the players are and what they hope to achieve. I find it illuminating and terrifying, but so important to understand.

Feel free to share this post, and subscribe for future updates. If you found value in this, I hope you consider a paid subscription. Paying subscribers help support the sort of research these pieces require.

NOTES:

1. I use the term queer, which was once an insult deployed against gay people of all sorts. Starting in the 1980s, however, the name began to be reclaimed by the community in a show of defiance. Of course, as with any massive and diverse community, not everyone embraces it.

I like queer because it feels inclusive—if you are anywhere on the spectrum beyond absolutely straight, you are queer. If you are gender fluid, trans, non-binary, or even just curious or questioning, you can be queer. You can be queer if you’re not in a romantic relationship and don’t want to be (asexual can be considered queer). Queer, to me, feels like the biggest, broadest umbrella imaginable, with room enough to hold us all.

2. I have made every effort to accurately represent the history and issues at play here, but I am not an expert in human sexuality or queer history. If you have additional information, or feel I may have taken something out of context, please feel free to share below in the comments. I’d love to get a respectful discussion going. Non-respectful comments will be deleted.

What I think hear you saying from this writing is because 'gay' life styles were widely practiced throughout man's history, (albeit pagen countries with also pagen religions) then that makes it an acceptable human expression of love closer to the love of God than the Christian church. Hmmm. So 2 things: 1. GOD and the Bible are the truth ...the plumb line for moral expression; it clearly states old and new testament that man lying with a man and woman with a woman are abominations in his sight (if you are a Christian you know where those scriptures are, in the New testament it's Romans 1). 2. In the history of God's people this sexual practice was never accepted by God. "There is a way that seemeth right unto man but the end thereunto is death" . Bottom line, God does not accept homosexual and lesbian sex as a higher mode of love; that is a lie against scripture and God...it is high level sin and must be repented of.

How does gender binary connect to capitalism